“…so what?”

My little sister asked when I showed her the new edit of my newsletter’s logo that I was crafting on Canva.

She was on her way to the gym when she noticed me seated at the makeshift desk I had turned our upstairs parlor into since moving back home, face inches from my laptop screen, fussing. She peered over my shoulder, and when she saw the rough draft, she oooooooh’d.

“You like this?” I rebutted.

“Yes! It’s so colorful. Love the clouds. The font can be a little simpler, especially because the background is attention-grabbing, but yeah. Mad cool.”

I didn’t tell her this was the sixth version of the logo. The night before, I thought I was satisfied with it, so much so that I posted the version onto Substack’s Notes to reintroduce myself to the algorithm. That’s usually how I know I’m happy about a piece I share: I post it. But the following day, I looked at the post like a nervous artist would and realized it still didn’t feel good. Something felt off.

“I don’t know. It’s not giving a 34-year-old with some life under her belt. It’s giving immature. Adolescent.”

She shrugged, struggling to see what I saw. “…It’s really not. It’s warm and imaginative. That’s literally who you are.”

My little sister, a powerful Sagittarius through and through, doesn’t make time to beat around the bush or to dress a first draft up real pretty — her mission is to make the thing, then focus on looks later. I am the complete opposite. I can’t even begin writing a piece if the font isn’t correct (slaps palm to forehead). I can get stuck in design mode off this ALONE.

“True—” I groaned.

“But so what? So what if it IS adolescent? We caaaares? We need that, too. Art ain’t always serious. Lighten up, girlie.” I took a deep breath and let the reminder sink in.

She began moonwalking out of the office, waving at me. “Get out of your head. It’s cute. You’re fine. See ya later.”

And there I was, left alone with my fears, sitting on a screen across from me.

Did I want to be cute? Warm? Whimsical? I mean, as my sister said, and which was of no surprise to me: that’s who I am, especially when I’m not trying. I am both delightful and seek to be delighted regularly. My engagement with the world resides along rose vines, romantic and sweet. There is plenty of room for passion that might look aggressive, and I have moments of cutthroat behavior.

But what I am, at my most regular, is delightful.

But if I understood these were some of my best parts, why did I treat their appearance in my art like a hindrance to my expanse?

If this is what exudes from my creative pores, why is it so difficult to accept?

Do you know what I miss? There was a time when I was more intrigued with what I discovered about myself through my work than I was about earning the world’s opinion of it.

That era, my most creatively fluid, was college. There wasn’t a thing I wasn’t making. I was writing plays and performing them, had an on-campus radio show, and wrote for the school newspaper. I watched every movie and attended as many shows as my allowance could allow.

My campus was in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, during one of the greatest innovations in creative output we’d ever seen and possibly the coolest thing I've been a part of. It was mere blocks away from a few art-based meccas in the neighborhood. Fort Greene, alongside Bedstuy and Crown Heights, had only just truly begun to experience the massive erasure of gentrification; it was otherwise still Black, still fly.

Every weekend, there was an event happening that engaged my senses without chilling me out. Spike Lee’s 40 Acres & A Mule, a few blocks away, hosted block parties like nothing. I got to witness and eventually work the Afropunk Festival when it was still heavily community-based and centered on the true subgenre of Black punk culture.

The digital age was fragrant, as YouTube and Vimeo created opportunities for people to make whatever they wanted. I began to play with filmmaking as a minor (my major was broadcast journalism), and it forced me to go to the streets and see the world from behind a camera.

This is how I began to interact with the world outside of my adolescent eyes. Around graduation, I realized I wanted to become a visual storyteller as well as a writer. I went to film festivals to watch shorts and hung onto our faves, who were just starting out with public recognition.

When I interned for Terence Nance during the debut of his first feature, “An Oversimplification of Her Beauty (2011),” his off-kilter, mixed-media approach to narrative storytelling made me realize the places the imagination can go and how accessible it is, especially for Black people.

I volunteered my time with Nikyatu Jusu (“Suicide by Sunlight”, “NANNY”) and Ja’Tovia Gary (“An Ecstatic Experience”), prioritized panels featuring Nuotama Bodomo (“Afronauts”, “Boneshaker”) and Jenn Nkiru (“REBIRTH IS NECESSARY”), and made myself known to Darius Clark Monroe. I attended workshops that could teach me how to see beyond the frailty of our terrains.

This prioritization of the Afro-surrealist Pan African (American) perspective, which was desperately needed and ran the indie space rampant, made me feel so seen that it expanded my appreciation for art and art-making.

I’d learn to measure great work with language that surpassed flirting with nuance; it defined grey matter. As filmmaking became a clearer path toward my creative identity, I was surrounded by aspiring art thespians who knew how to alchemize numerous mediums and create works of art that consistently challenged the mundanity we were walking comatose in.

And yet, the stories I found myself writing and the characters that followed me across educational institutions and coasts as I moved from Brooklyn to New Orleans and from New Orleans to Los Angeles did not feel like they echoed that DEPTH. They did not match my idea of the matured refinement of art’s possibilities.

They were tender and romantic. Whimsical and endearing. Sensual and passionate. They didn’t feel textbook political. If I had to write artist statements, the language wouldn’t drag you to corners of the Earth you didn’t know existed behind your eyes.

Some of our most favorite and stunning writers, filmmakers, musicians, fine artists, innovators, etc., were unwavering in their practice. Why couldn’t that be me?

Me, who found conversation with flowers and the night sky. Who whispered short stories under her breath with her head to the pillow like a child with a wish. Who people-watched in hopes of a surprise. Who ate longing for breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

My relationship with my queerness opened up an edge to me. I explored her some when I got into graduate film school; for every writing assignment I was given, Black women loving each other maintained the primary narrative. She was incessantly expressing her excitement that I finally took her seriously. She provided a healthy hunger for self-exploration that I hadn’t felt in a long time. She answered questions I thought I’d never ask.

I loved it, and after graduation, I was proud of the body of work I emerged into the real world with. In fact, my understanding of my deep affinity for women excited my hand at writing them as they romanced me at the same time.

Something began to make sense and draw me away from the expectations I felt I needed to meet for an unseen audience.

But, the real world. The heinous theme that came back around. Frameworks that weren’t mine eclipsed my idealism, and suddenly, art had to become serious again.

A “career” called me, working on film sets and eventually in a studio. And suddenly, I was within the margins of making movie magic and seeing just how uncreative movie-making can be within an industry. I left magical places to enter conventional ones.

That made me cling to surrealist forms of artmaking harder. It was as if I’d built this idea that surrealism, combatting the plain and dismal expressions of our society, was always the answer. That it had to be as astute in its indifference as conventional entertainment was astute in theirs.

That practice never made room for my ideas of romance, tenderness, and whimsicality. How narrow I had learned to approach art and expression. How unfair of a world I had made for myself to constantly disregard what mattered to me…

Last February, a month after ending my situationship and returning to Los Angeles with this newfound determination to make the city work for me one last time, I prioritized what brought me sustenance: art.

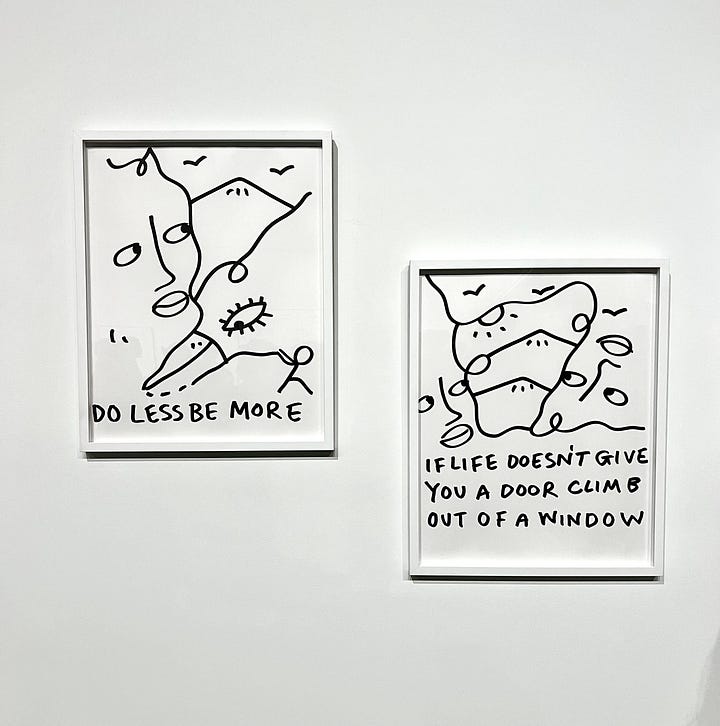

My heart and eyes were lighter. I was seeking inspiration that didn’t remind me of the industry or the love I left in the Bronx. I attended Shantell Martin’s “Intimate Whispers” show and toured the artwork about three times to gather my feelings about it.

It’s impressive because Shantell has made such a stunning name for herself through her black-and-white line drawings, leading to incisions of faces drawn with buggy eyes and round lips in between.

I’ve known of her work since college (funny full circle moment, for that was my creative evolution), and for all these years, she’s maintained her signature style but moved from paper to wall prints. From small to large scale. Line drawings that art teachers would probably start people off with who’re interested in tapping into their artistic hands.

Shantell has managed to make this her thing, and it’s truly one of a kind.

I attended because Shantell was making her first departure from her art form since hopping onto the scene: she was incorporating color. And they were lovely insertions. The colors, tones of deep green, purple, and blues… felt like delightful allegations from the black-and-white. The characters felt alive, like wandering spirits with whispers if you stood close enough to them.

If anything, there was an intimacy that held your gaze despite the simplicity of the line drawing. Some pieces incorporated affirmations: “Do Less. Be More.” Another looked like a map. And then, she had a manifesto/diary entry framed beside the work, a moment of vulnerability as she attempted to gain clarity with herself. The pieces seemed simple but held plenty of maturity in their contours.

At one point, while I stood in front of a piece that called to me and held my phone up to take a picture, an elder Black woman asked me, “Are you making content?”

Her name was Sheila*, a retired 65-year-old UCLA professor of contemporary art who wanted to remain in the know of the evolving artistic landscape of Los Angeles. We ended up having a wonderful conversation, as I revealed that I, too, wanted to be deeper in the realms of art’s society, especially Black artists.

We befriended each other, and a week later, she invited me on a head-to-toe tour of the Hammer Museum. It was a weekday afternoon, so it was relatively empty, and it felt like we had the place to ourselves. We walked leisurely through the museum, and she taught me about art like I was her pupil.

She told me stories about how she tumbled into the field, what it was like being a Black woman who never planted her feet, and the joys of being present for the explosion of Neo-Expressionism, an art movement around the world during the late 1960s to 1970s that detached from the “intellectual and minimalist” portrayals of art by leaning deep into expressive and representative pieces.

“Art, for such a long time, has been gatekept by White people who decide what’s good and what’s not. And most times, none of it actually matters,” she told me as we walked through an exhibit that hung up textured, beige plaques and placed old computer technology on display.

I looked around, unimpressed, at this massive room holding real estate in one of the most reputable museums in the country, for something anyone (literally, ANYONE) could have done. “See?” Sheila said, pointing at an old ‘90s PC, CD-ROM drive and all. “I got this at my house. Yet, here, it’s a ‘piece’.”

I don’t remember what I asked her after that, but I remember her response: “What’s popular changes so often that I wish I could tell more artists to do what they want.”

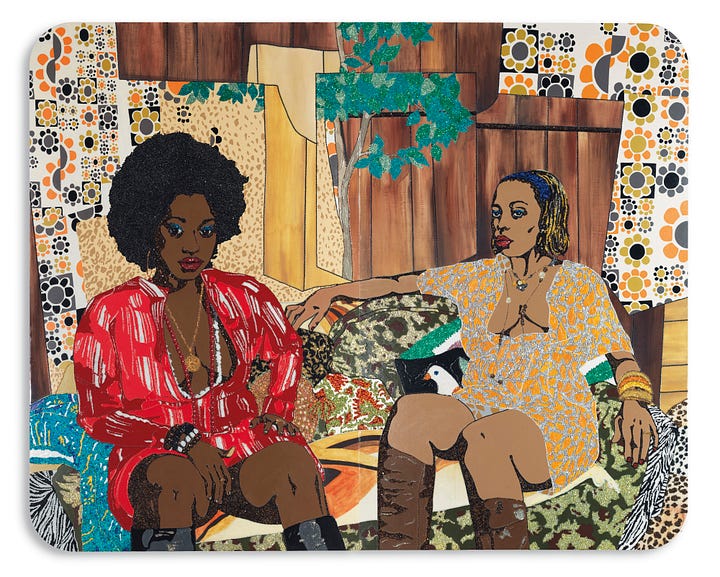

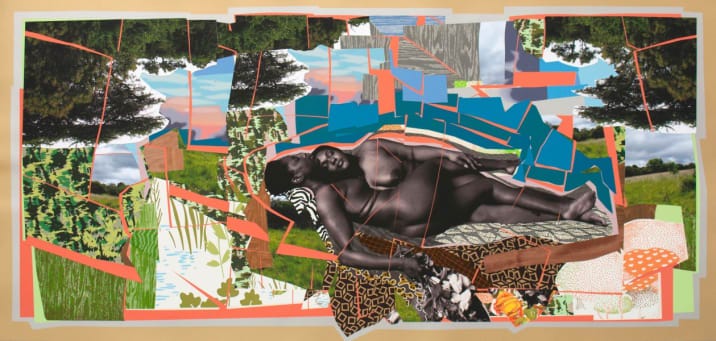

In June, Sheila invited me to Mickalene Thomas’s latest exhibition at the Broad Museum in LA, titled “All About Love.” If you’re not familiar with her work, Mickalene is another Black queer contemporary artist whose scale knows no bounds.

Often crossing territory between each other and always making it fit, with bold use of color, mixed textures, and electric displays of Black womanhood, she has taken photographs, developed installations, assembled collages, built sculptures, and dressed canvases, matching her curiosity to the process that suits it best.

While many artists do this, I believe what sets her apart from her peers is her remarkable balance of sensuality, whimsy, passion, and charm.

Everything I’m hesitant to show (hangs head).

I’d never attended an entire exhibition of her work before. I’ve only ever happened upon a piece or two included in a curated art installation or seen it online. Never like this, never taking up a large portion of the bottom floor of one of the best museums LA has to offer.

Sheila was stepping out on her own faith. Using her connections and education, she wanted to curate exhibition tours, artist studio visits, and demonstrations for a small group of aficionados interested in maintaining a closeness to the medium.

She had mentioned to me when we grabbed lunch after that Hammer Museum tour that the art world in LA was picking up speed again, and she missed the buzz and luxury of having students to bridge the gap with. So, she’d do her own thing and asked if I’d be there for support at the first meet-up. Of course, I said yes—not just as an extra head, but because I wanted to learn, too.

And what I saw floored me.

Over 90 pieces throughout the years of her artistry on display, Our tour guide introduced us to Mickalene’s world by starting us outside what looked like a Philly home, like the ones she grew up in.

We entered into a living room mock-up reminiscent of how our Black mothers furnished our homes growing up: antique couches, deep-colored carpets, wood carvings, and more. Except it was divinely eccentric. The purpose was to illustrate that her love for Black womanhood started here, in this intimate space, with the Black women who raised her.

As we moved through the exhibition, we witnessed how it remained the thread of her curiosities across mediums. She loved her upbringing dearly and every person near and far who brought her along for this ride called life. You can see that this exhibition was a massive THANK YOU, a level of appreciation we hadn’t seen before.

It is also a radical subversion to classical art, reminding me of the impacts of Neo-Expressionist artwork. Some of the poses these women take are reimaginings from art history but enhanced by the cultural beauty of Black women. Challenging the box of same-ness that art had forced onto its industry for so long. It is both a strange acceptance of the art that came to pass before us and a bold introduction that this is art NOW.

She transforms the variety of everyday Black women through the “freedom” ages, whether they were church-going mothers, porn stars, aunties, lovers, sisterfriends, and even herself, into literal plaques of art. Elevated by bedazzled sequins and jewels. Drawn over with circulating lines and scribbles of color. Sat over eclectic, collaged backdrops surrounding them. Unabashed mixtures of patterns. Social justice pieces that pierced your spirit to look. Consistent energy exudes degrees of confidence and self-regard. Intimacy and a raging sexual prowess. Remnants of teenage dreaming highlighted through the pop culture references and stacks of books aligned within the bedroom installation—

It felt like Mickalene made space for her universe, and we were invited.

I was transfixed. I had never seen work like this, which held every era of her evolution so close to the heart that it spilled into the work. It felt like freedom—the kind I so desperately wanted to taste. It was unwavering, bold, and heavily breathing with life.

I wish I had documented my feelings sooner, maybe ripe after the viewing. Mickalene follows a trust that, as I mentioned, stands out. You KNOW you haven’t seen work like this.

How beautiful it is when you can hold your vision in front of you and smile first. Exhale from the relief of THAT trust, the one where you are safe within yourself to express the imagination. And to refine it from infancy to maturity. Because maturity looks like stretching in its process from a place of intrigue, frustration, and allowance.

Even if what it looks like reminds you of the tools you used to decorate your construction paper as a child. I mean this with full respect, it feels like all ages of Mickalene co-exist beautifully, with her adult self as the mother. She made it okay for work to transport you back to a time when you were allowed to have FUN with glue and crayons and glitter. To a time when your purity meant trying sex for the first time. To a time when you rented your own home and redecorated it like your mom and n’em.

I walked out and spent the week envisioning a moment for myself that would soon become my practice, my priority. I was on the way, on the precipice of this. Once you know something, you can’t unknow it.

And how beautiful it was to know that your adolescence can be your compass.

I want to end this by mentioning that there was something I missed. It’s crucial:

Every single artist whom I hold near and dear to be an innovator in the arts had to work insatiably at making consistent space for their voice to exist in a container that made room for them. It’s fickle of me to look upon them with this deep yearning to match their audacity when the true inheritance of their offering would be to stand, willing, in my truth as they had.

It has never been and never will be, about needing my work to look like theirs. This is where my immaturity clung to the ritual of wanting to be mothered and fathered.

This journey has always been about coming home and making my space one I am eager to return to over and over. Even when I think about my leaving Brooklyn five years ago, only to return again. I got to live out my adventures, learn the new and evolving ways in which I am capable, fall in and out of love, and return with a hungry belly. This is about me feeding myself.

There is community, yes. But even they cannot lead you to the water to drink. That will have to be you. The suffering I endure is the sheer resistance to the responsibility I must embrace in being the artist I am and that I need.

I wish I could tell you I’ve since rid myself of the judgment that my voice is less important because it’s not surrealist like my favorite artists portray. I’d be lying, and there’s no need for that.

When I finished the final version of my logo, it was a fight to remind myself that any edits I make should be because the visual language doesn’t bring me closer to myself. Anything other than that, anything that dimmed the imagination of the work I was doing, was a lie propped up by a belief that disregards the sweetness of myself.

This forced me to return home to the elements that most represented me: the pungent and warm hue of pink, the textured grain, the clouds, and that cutout selfie of me looking towards an unseen sky as I wondered. These elements were essential aesthetics that encapsulate me when I’m to myself. Everything else would be decoration.

The branches of leaves were a touch to demonstrate my consistent love affair with greenery, as well as a special spark of color to contrast the warmth of the background; it’s an imprint that follows me across all my graphic designs. I am also a woman who LOVES a good doodle session. I don’t know what it is about a doodle line, but that seems to follow me across designs, too (perhaps Shantell had a greater impact on me than I knew). I drew those outlines along my locs as a last-minute attempt to add extra whimsy.

The wording, which was also a tough decision, resulted from my choosing simplicity. It provides a pristine, almost feminine touch. I tested many pairs and landed on this one, which is a great leap from the attention-grabbing font I used in my earlier drafts. They shouted, while Recoleta and Times New Roman felt like invitations.

Finally, after staring at it for about an hour, leaving it alone, and returning to it the next day for one last inspection, the design felt correct. I felt like I had found IT.

I also discovered that this is my artistic process. It is how I make room for myself to establish work safely and excitedly. I have to be prepared to watch it evolve and trust that it always will because it is growing as I am. What a relief to know that it can only get better and that, eventually, I will meet myself.

I return home.

I’ve been leaning in, scared. Every time. Through the logo, through the video vignettes I make when my lens eye is captivated, through the writing of my latest short film script (I’ll talk about this soon), and yes, even through these damn newsletter posts.

I realize this fear wants me in the fetal position, but I am also committed to meeting myself. I have to be. At this ripe moment of my life, where there’s a door held open for me to throw out conventional distractions so I can let the real light in, I have to finally give me a CHANCE. I just have to try. I have to see what’s behind it.

Embracing yourself is not neat or linear. Sometimes, it looks like returning to things that “adulthood” forces you to forget. Sometimes, it’s a lot about begging for permission in the wrong places until you realize the permission granted comes from you. It is a marathon of yes’s and no’s and wins with some losses. It’s a humbling human experience that, as aching as it can be, is the greatest opportunity to grow confidence that, despite it all, you can.

You just CAN. What? Well, whatever.

You can do whatever. And it might not kill you.

You might look childish, but you’ll be smiling at the end.

Like a Shantell Martin line drawing across a wall. Like a Mickalene Thomas collage of Black women who look like her aunties threaded with glitter.

Like a logo with clouds that tells people you are a dreamer.

You can do whatever, and you’ll be smiling at the end. It will be enough.

Share this post